Boy From Buchenwald

Kirkus Best YA Biography and Memoir 2021

Sydney Taylor Award Notable, 2021

Sheila A. Egoff Children’s Literature Prize, BC/Yukon Book Prizes

Gold Standard Selection, The Junior Library Guild

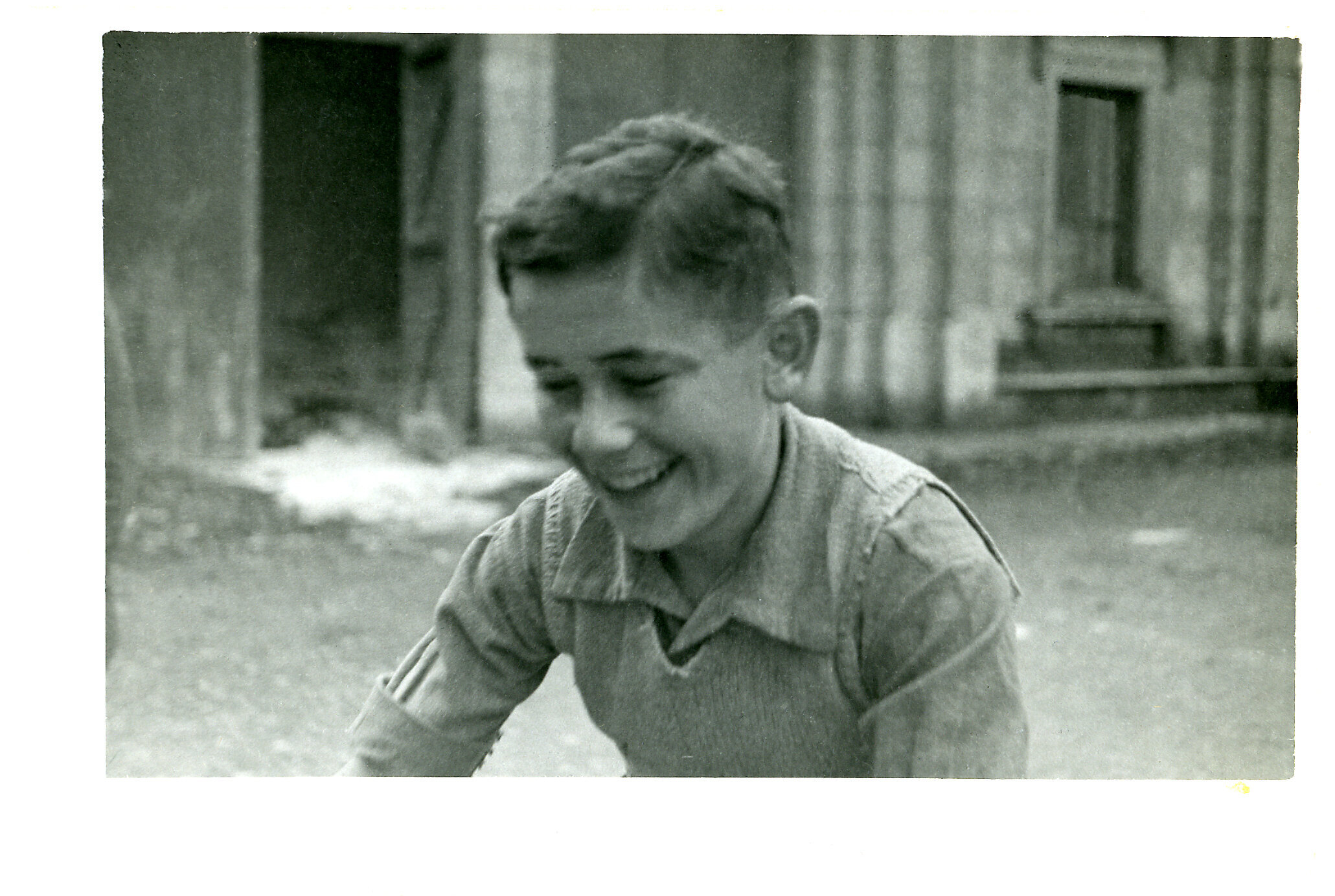

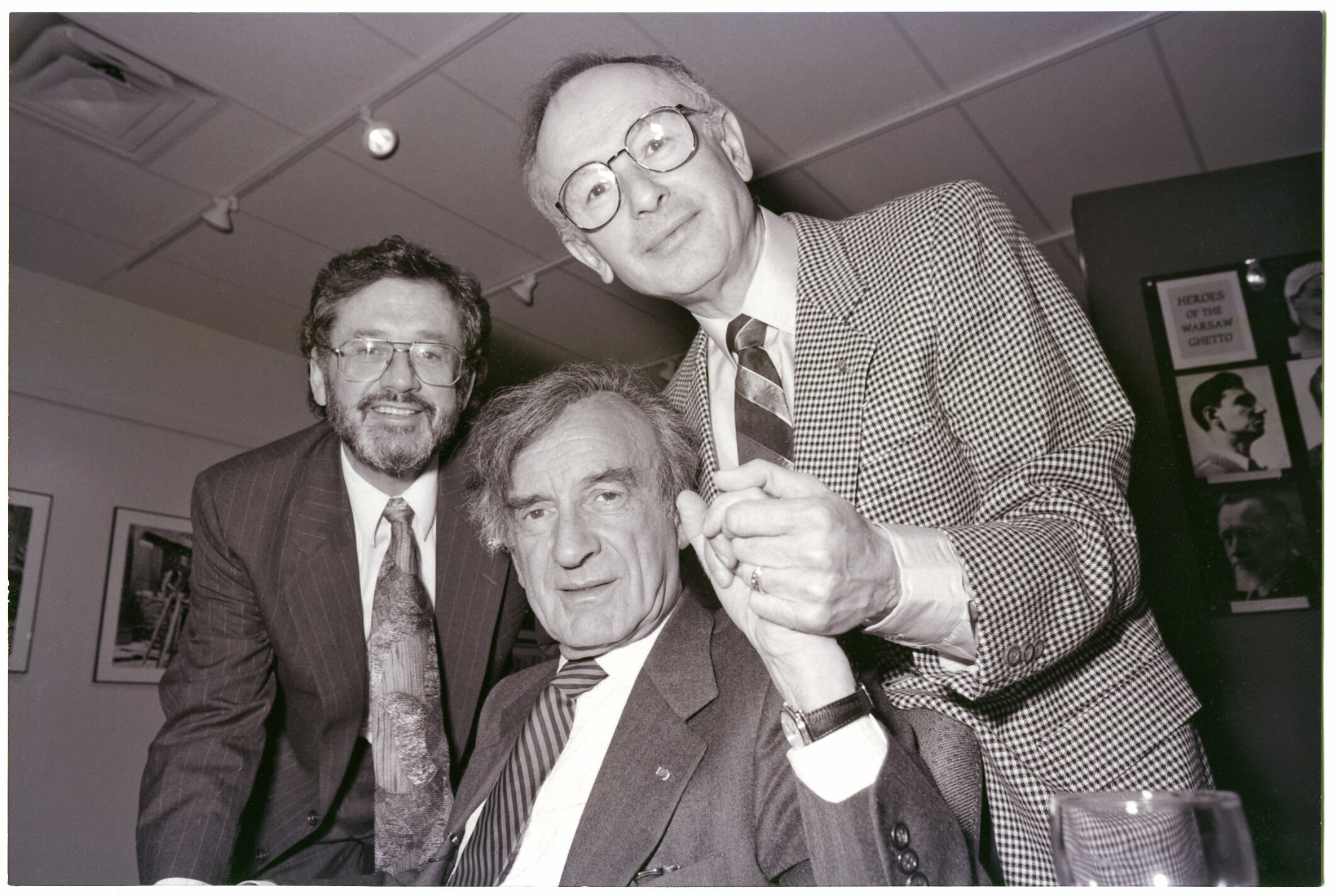

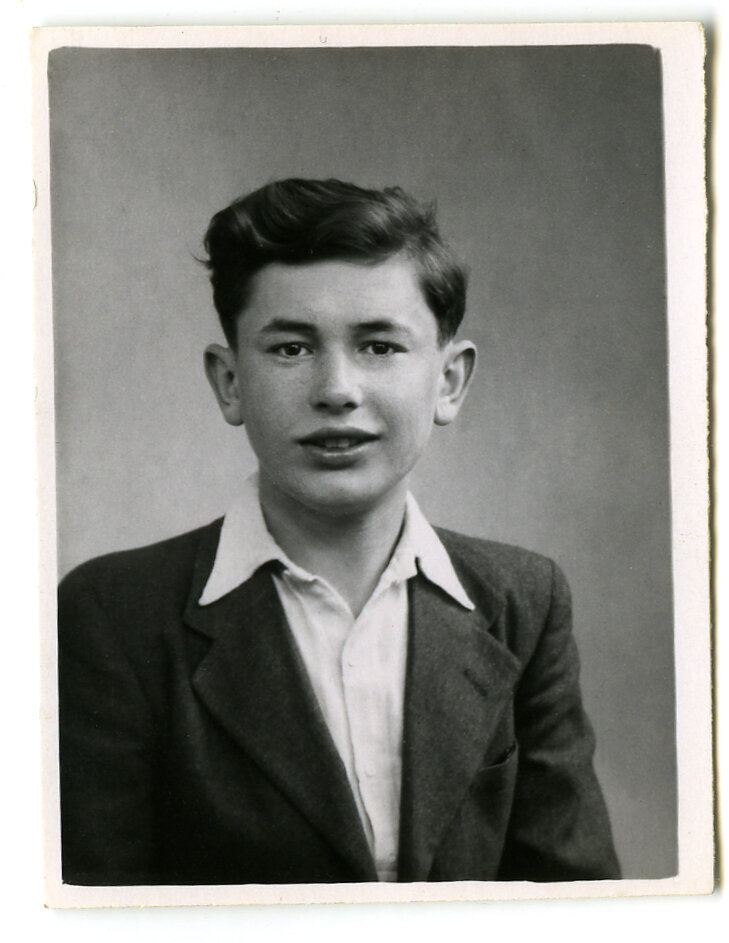

When American troops liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp on April 11, 1945, they made an astonishing find: more than a thousand Jewish boys under the age of eighteen. These boys, protected by the camp’s resistance movement, had spent most of the Holocaust starving, tortured, witnessing the most extreme brutality, and having no idea if their families were alive or dead. Among those boys was fourteen- year-old Romek Wajsman, a Polish child who had survived by working as a slave laborer for a German munitions factory. These children, dubbed by the media as the Buchenwald Boys and including Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel, were angry at the world and turned to violence: stealing, fighting each other, and struggling for power. Few thought they would ever be able to lead functional lives again. But everything changed for Romek and 427 of these boys when they were brought to a home for rehabilitation in Écouis, France. This is their story of overcoming the worst of humanity to embrace life again.

Bloomsbury, USA and Canada, May 2021; Destino, Spain, June, 2021; Euromedia Group, Czech Republic, May, 2021; De Boekerij, Netherlands; Mondadori Libri, Italy; Saída de Emergencia, Portugal, October 2021; Patakis Publishers, Greece, October 2021; Weltbild GmbH & Co, Germany, May 2021; EKSMO Publishing House, Russia, August 2021;

Foreign Translation Rights, Jessica Buckman, The Buckman Agency at Ampersand, London, UK

Media Inquiries: Ksenia Winnicki (USA); Fernanda Viveiros (Canada)

“The stories of his many narrow escapes from death are incredible, and he effectively describes his feelings of disorientation when sent with other boys to France after the war to be helped by a children’s aid society. Despite the boys’ bad behavior, the society believed they weren’t irrevocably damaged, like others did. Readers will get a glimpse of Waisman’s inability to fully process what he’d been through and his rage at not being able to go find his family.”

- Booklist, starred review

“Lyrical writing focuses on the aftermath of the Holocaust, a vital, underaddressed aspect of survivor stories.”

— Kirkus starred review

Excerpt

And wild animals shall meet with hyenas; the wild goat shall cry to his fellow; indeed, there the night bird settles and finds for herself a resting place. —Isaiah 34:14

THE MAN WORE a crisp, clean, and long piped blue coat with brass buttons, a red swastika and medals, which I came to learn indicated his rank with the Schutzstaffel, also known as the SS, a paramilitary unit of the German Nazi Party. The man’s sky-blue eyes were narrowed, his forehead furrowed, and he was pointing at me.

I was marching with the men to the munitions factory in Skarżysko-Kamienna, Poland. The factory was named Hugo Schneider Aktiengesellschaft Metallwarenfabrik but every-one called it HASAG.

I worked at the factory, as did thousands of Jews. All of us were slave laborers. None of us was paid. My job was stamping the initials FES onto artillery shells for the Wehrmacht, the Nazi German military. I could stamp 3,200 shells in each of my twelve-hour shifts, which I worked six days a week. When I started at HASAG, I was eleven years old. The year was 1942. For the first few months, I was working so hard, the skin on my hands chafed so much, that I bled. But if I stopped working, I knew—I had seen the Nazis and the soldiers from other armies who worked for them do it to others—I would be shot dead. I worked until the wounds became calluses that hardened like shoe leather.

I usually worked the day shift, which started at seven am. But every few weeks, I was on the night shift, too.

As I marched along with the men on my shift, I lifted my knees up high, hoping to show the SS man that I was healthy. But the SS man nonetheless waved at me to step out of line. He was shouting, “Raus!” which meant “get out” in German. The German language actually wasn’t very different from Yiddish, which I spoke with my family at home. So I knew German words, at least a few, when I started at HASAG. By the end of World War II, I could pretty well speak German fluently.

I swallowed the lump that had formed in the back of my throat and did what the SS man said. He walked toward me, stopping so closely, I could feel his sticky, warm breath on my face. I smelled his breakfast of eggs and onions when he bent down to shout at me again: “Raus!” He then spun me around and dug the butt of his rifle in between my shoulder blades.

“March,” he then ordered.

I pinched my eyes shut, knowing exactly where he was leading me: to the pickup truck idling outside the front gate of the barracks where we slave laborers were imprisoned when we were not working.

I knew why I had been selected, too. For a fortnight, I had been drifting in and out of sweats and chills from typhoid fever. When my fever had broken and I discovered I was still alive, I suspected one of the men in the barracks, perhaps Papa’s friend the kosher butcher, had kept me hidden under straw and given me water. You see, Lithuanian guards who worked for the Nazis came at seven am and seven pm, when the night-shift men and the day-shift men traded places, making sure no one was hiding in the barracks or sick. Somehow, I had not been discovered.

As we neared the pickup truck, I opened my eyes. “Another one,” the SS man spat to the men guarding the truck.

The SS man then ordered me to climb into the cargo bed. There were about twenty other men there, skeleton thin, their skin blue from malnutrition, many with scabs on their faces from the various diseases that flowed through the barracks the way the Kamienna River flowed through Skarżysko-Kamienna. There were some men whose skin was yellow: the slave laborers who worked with picric acid, an explosive related to TNT. Picric acid turned these workers’ skin and eyes yellow and eventually destroyed their kidneys.

I knew we were being taken into the forest to be killed. First, though, we would have to dig our own graves.

“Another rat,” I heard one of the guards say.

“Worm food.”

I shivered with fear. I felt urine dripping down my leg. I knew I had risked going back to work when I was still pale and slow-moving. But I had no choice. If I hadn’t, eventually my absence would have been noticed.

When my brother Abram worked at HASAG alongside me, he would pinch my cheeks before morning roll call so I looked well and would place cardboard in the soles of my shoes so I appeared taller and older. The Nazis didn’t really like children working, and they sent many away, likely to their deaths.

I was sitting in the cargo bed of the truck, at the very rear, staring out, first at the barracks—long, gray, and black—then the sky above them that moved like smoke. My eyes caught a cloud, traveling faster than the others. It looked like an island in the midst of a stormy sea. Suddenly, the shaking, the tremor that had dug itself right down deep into my bones, stopped.

I could see light, like the rays of sun, which, looking back, had to be impossible on that day.

I felt something wrap around me then, like a soft blanket, bringing with it a calmness, a lightness that I hadn’t felt in the last three years, since before the Germans stormed their way into Poland, occupying it, making it theirs.

I was going to die, but suddenly it didn’t matter.

I started to remember things I had forgotten since I started at HASAG: Mama singing me “My Little Town Belz,” Papa wrapping me inside his tallit at synagogue, playing soccer with my older brothers. I even heard the voice of my sister, Leah, telling me we would meet again.

That dark island cloud then turned into wings, like that of one of the angels. Azrael, I mouthed. I could feel Azrael, the angel that transports souls to heaven, folding me, ever so softly, into himself.

Flooding me were memories of love that I knew would stay with me wherever I went.

I no longer clung to life.

I heard mystical sounds of wind chimes and tiny bells, even a chorus of singers.

I exhaled, knowing my breath was leaving.

I was in such a state of beauty and wonderment that I didn’t feel at first the strong hand that had clasped onto the collar of my jacket.

I was being lifted off the truck.

The German man, the one who often came to HASAG to oversee the Jewish slave workers, the one I was sure held a high position with the Nazis, because the Germans would stand up straight, click their heels, salute him, and call out “Heil Hitler” when he walked by, this man was removing me from the truck. When Germans from Germany would visit the factory, he would show me off, commenting on how quickly and efficiently I worked. He was shouting at the SS man with the gun that I was too valuable a worker, that I worked faster than two grown men put together. I needed some time to get better. I had to be saved.

The soft music stopped and Mama and Papa disappeared. Azrael was gone, too, the sky dark gray, spitting out rain.